This morning, July 15, 2013, I woke up to an important facebook post by my dear colleague Tamaan K. Osbourne-Roberts, M.D., family physician and leader in Colorado. I asked him if I could share his essay in my blog. Thank you Taaman for your words:

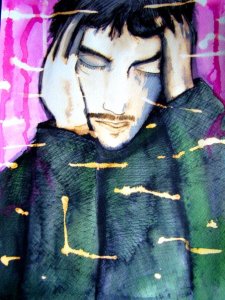

More than anything else in my recent memory, I’ve been tortured and sickened, in the deepest parts of my being, by the verdict in the Trayvon Martin case. While I certainly share the same revulsion many feel at the gross legislative perversion that is Florida’s interpretation of a “Stand Your Ground” law and the legalized vigilantism it now seems to allow, the thing that disturbs me the most, the thing that is giving me chest pain as I write this and that is starting to keep me awake at night, has little to do with the legal details. It has to do, instead, with how this case applies directly to me, and to my family. It is a deeply personal, and intensely frightening, realization about my place, and my children’s place, in America.

With your indulgence, I’ll explain. But I must warn you, the things I am going to discuss, while true, are not going to be easy to read, or pleasant to contemplate.

If you’re still with me after that last sentence, let me start with a little bit about my background.

I am a person of Afro-Caribbean ancestry, and a first generation American. My parents, now naturalized citizens, both hail from the country of Trinidad and Tobago, a petroleum-producing nation near Venezuela, and one of the few countries in the world more diverse than the U.S., with no true majority population. The people, and the culture, are a harmonious blend of Indian, African, European, Chinese, Arab, Native American, and other influences; at least four continents’ worth of bloodlines flow through my veins, and because of this, I was raised with an innate respect for diversity. I was also raised with an innate sense of privilege. My mother, a teacher, comes from a successful Caribbean political family; my father, a 22-year veteran of the U.S. Air Force and the author (at the time) of the systems accounting handbook for the entire U.S. Department of Defense, initially attended the same high school as his home country’s first prime minister. As a military brat, I was fortunate to be raised in incredibly diverse and accepting neighborhoods, where everyone saluted the same flag and the only segregation in neighborhoods was by rank. Because of all of these influences, I was raised, at least initially, with a bare minimum of race-consciousness.

This approach of privilege and diversity has hardly changed for me as an adult. I went to one of the best colleges in the nation, where I met my wife, and then on to med school to become a physician who works primarily with poor, Spanish-speaking patients. I am a left-of-center, socially liberal, fiscally conservative yuppie who lives in a new house in a well-to-do neighborhood in a majority white, liberal, very yuppie city. My neighbors are also professionals, mostly doctors, lawyers, and engineers. My friends hail from all corners of the country, and the globe; pictures of my wedding look a good bit like a United Nations gala. I climb mountains on the weekend, own multiple items from REI, wear fleece, like to cook and scuba dive, and drive a Honda. I have spoken on the steps of our state capitol, and been to Congress to lobby legislators. In almost every way, I have met society’s expectations of success in my manner of speech, thought, dress, and comportment

By all rights, I should be able to forget that race even exists.

Except that I can’t. Because, despite my overall success, I am exposed to such an emasculating stream of discrimination, racial profiling, and intimidation based on my appearance that the world sometimes seems determined to prevent me from ever living in such blissful ignorance.

Please, allow me to illustrate by providing three salient, detailed, and very real examples.

Example 1: At age 20, while my family was away for my aunt’s funeral (I couldn’t attend due to academic engagements), I had driven my car at the time, a “hooptie” Oldsmobile, to my favorite coffee shop in a seedy part of town, where one of the back windows was broken out and my radio stolen. It was the first time I’d ever been a crime victim, so I went to stay at a friend’s house that evening, and then went to do some studying at a sit-down restaurant in one of the nicest parts of town, in part to cheer myself up since my normal supports were away and I was already sad about my aunt. As I pulled out of the parking lot, a police officer “eyed me hard” and then pulled me over immediately. He immediately (and, in my opinion, boldly) indicated that he stopped me not primarily for a broken windshield (which are incredibly common here in Colorado, due to the weather), but even more because young men driving cars of “this type” with broken rear windows had often stolen the cars. (At that point, I informed him about my radio). He took my information, ran it and found nothing, but nevertheless filled out a report of some kind, coming back to the car to confirm the spelling of my name. I spoke with a friend who had worked as a civilian for the police department, and he indicated that this represented a “contact sheet,” meaning that if the police pulled me over again, there would be a record in their system that they had had contact with me. Lovely. As a reward for having been victimized by a criminal, I was now going to be on the police’s “watch list”…

Example 2: In my senior year of college, a good friend drove me to get doughnuts in the neighboring town at a locally famous doughnut shop, at about 3:00 AM, just as the first batches were coming out of the fryer. As we pulled in to park, I noticed a police officer again “eyeing me hard,” but tried to ignore such. We walked into the doughnut shop; the owner was in the back cooking and did not hear us come in, but he had a police scanner turned up rather loudly, which we listened to as we waited. Suddenly, on the scanner, they read out the registration info for my friend’s car; worried about whether his car was being stolen or broken into, we ran back down the hill, where two police cruisers swooped in, discharging two cops with their hands on their holsters, who instructed us to stay where we were, with our hands visible. We were then instructed to put our hands on the hood, we were frisked, and my friend was queried as to what we were doing here so late. We were then marched back to the doughnut shop, where the shop owner was queried in the same fashion, and vouched for us. (Interestingly, the police never said a single word to me directly). As we drove back to the dorm with our doughnuts, my friend, a politically right-of-center Caucasian guy of Italian descent, looks at me, and, unprompted, says, “I hate to say this, but I’ll bet you that if you weren’t with me, none of that would have happened.” I had to reluctantly agree with him.

Example 3: Just this last year, my wife and I built our “forever house” in a new part of Denver that used to be the former airport. Excited to see it going up, we would stop by the building site regularly to take pictures and monitor progress. One evening at about 9:00 PM, as I stopped by to admire my future home, I saw headlights pull up directly behind me within 30 seconds of my stopping in the street. Thinking I was blocking someone who wanted to get past, I tried to pull off to the side, at which time I saw lights flash, and the now-obvious police car pulled me over. The officer immediately asked what I was doing there “at that hour” (mind you, other people already lived in the neighborhood on adjacent blocks), detailed that there had been a series of construction robberies recently, indicated that several “Hispanic guys in hoodies with a pick-up truck” had been seen in the area, and asserted “when you see something like that at this time of night, they’re always up to no good.” (I opted not to point out that I was not Hispanic, not wearing a hoodie, and not driving a truck). Again, he took my information and ran it through the computer to see what he could find, and then let me go. All this, despite the fact that my city councilor, my police chief, and my mayor are all African-American men…

These are just some of the examples of injustices I’ve been forced to endure because of my appearance. This is to say nothing of the many smaller indignities I face on a more regular basis: being repeatedly followed by police cars as they run my plates hoping for a “hit,” being asked for my ID to use a credit card when no Caucasian patrons ahead of me in line are asked for such, being asked what sport I played in college as the first follow-up question when someone finds out my alma mater. (My current answer is “Biology.”). But it is my encounters with racial profiling within the legal system that leave me the most frightened, as they represent not just indignities, but the potential for real professional and even physical harm, both to myself, and as my children grow up, to them, as well.

And we have just seen the potential to administer that sort of harm devolved into the hands of any racist Florida citizen who chooses to ignore police advice and follow someone based on their own subjective prejudices about whether they “belong” or “should be there.”

Considering just what this means has been excruciating. I have long known that I will never qualify for “white privilege.” And by “white privilege,” I don’t mean some nebulous, generalized, academic concept of “built wealth” or “controlling the reigns of power” based on historical colonial realities; my career and my background have given me better-than-average access to both adequate wealth and respect within my community, and I haven’t any qualms about my level of privilege in those respects. What I mean by “white privilege” is the fact that, because of my experiences, I will always feel my blood pressure rise when I see police, even though I have done nothing wrong; the fact that I have to think long and hard about the neighborhoods, and even the parts of the country, in which I can live to minimize my children’s exposure to prejudice; the fact that I will never feel wholly confident about a loan’s interest rate, or a teacher’s evaluation of my child, or a doctor’s evaluation of my wife, or any of a range of other circumstances where studies have shown that generalized racial bias exists, without going over such situation in painstaking detail to ensure that no bias exists in the given individual circumstance. When I talk about “white privilege,” I mean the absence of needing to think about these things.

But there is a real difference between those sorts of things, and what this case turns “white privilege” into. It elevates the concept from simply being an inconvenient double-standard of worry, to a partial protection against a state-sanctioned, vigilante-administered death penalty, without even the barest bones of due process. A protection that, by virtue of our appearance, my family does not have.

For me, what happened to Trayvon Martin is not a far-off news story in a far-removed courtroom, or an interesting theoretical argument about “burdens of proof” or other legal concepts; it is an inescapably immediate, chilling, frighteningly real affront to my, and my family’s, personal safety.

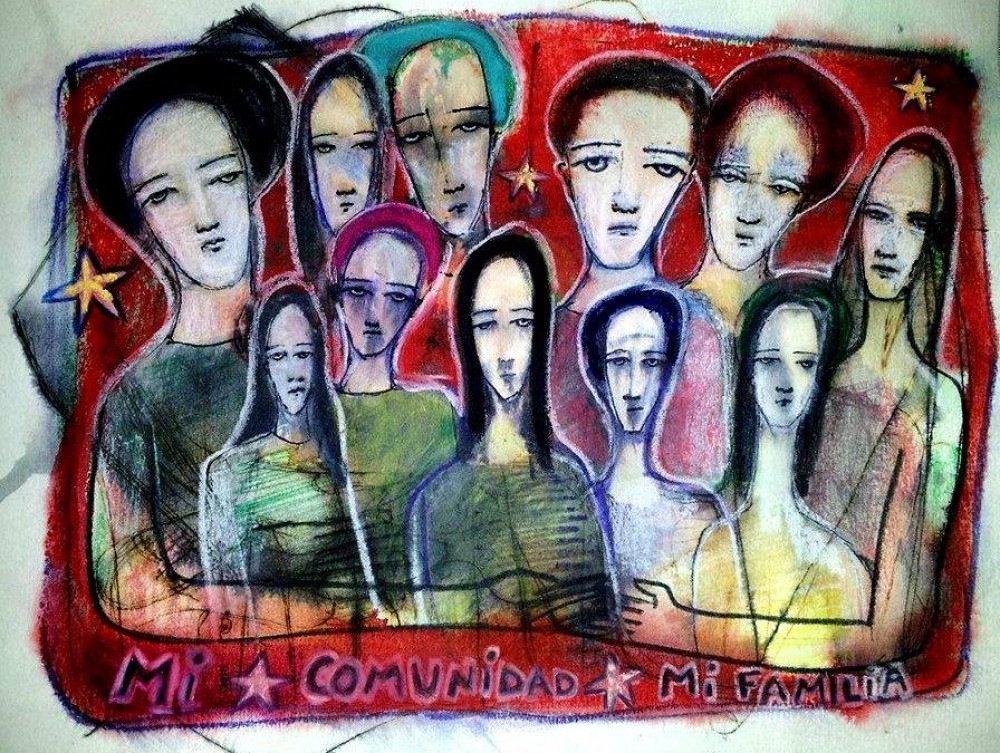

I am even more sickened when I consider my role as a parent of black children. When I was a teenager, I never understood why my mother, given her general bias against including racial thought in our daily lives, wanted to bring up race when talking about who I was hanging out with, where I was going to hang out, and what would be happening there. She had always placed great trust in me, and I resented her protectiveness and warnings that my appearance put me at higher risk, and that I had to be more careful than my friends. But now, with my own children, I “get it,” and following this verdict, I “get it” even more keenly. And it’s infuriating, scary, and painful, because how do you prepare your children for this? At my core, I know that most people in my community are good and not harmfully biased, but how do I advise my children to remain open-minded to the majority of folks they will meet, while at the same time protect them from the few zealots who could do them serious harm? Every time I see a picture of Trayvon, I can’t help but insert pictures of my own gloriously cute, bright, and incredibly sweet little boy and girl, and know that they’re at risk, in a way I would do anything to protect them against. And because of that, I’ve got to find a way to advise them, to guide them in a way that they don’t end up disheartened, jaded, or indiscriminately racist fools, but that still somehow gives them enough caution and presence of mind to know how to protect themselves. I resent this more than I can begin to adequately describe, because this is a nearly impossible task to ask of any parent. But, somehow, I’ve got to try. I’ve got no other choice. I’m their father, and I owe them that.

And considering this impossible task is likely to keep me up with chest pain for a number of nights in the near future.